Perhaps one of the finest clock museums in the world belongs to the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers in the UK. The Company started in 1631 while the library cum museum started in 1813/1814. When I entered the room, I was surprised at the relatively small size of the room, but it was crammed with over 600 watches and clocks. That said, all were sealed away and there was no ticking sound. At all. For which I am thankful, otherwise would have gone quietly mad.

As it so happens, i was telling my eldest that a clock is also a computer. After all, it takes a set of inputs, has a set of translation and calculation engines and produces an output that makes sense to humans. Perhaps the concept of measuring time is one of the crucial ways that humans have used to civilise themselves. I know, I know, there is the tyranny as well, but meetings, appointments, navigation, tasks, activities, all have now been governed by clocks. As a matter of fact, I read this book on how clocks were used to calculate Longitude some time back and it was brilliant. Have to do a review for it one of these days. Anyway, as usual, took too many photographs but am only showing some of them here. For the rest, please see the full slideshow in bigger resolution.

As you enter, you see that the museum is actually a long room, about 40 feet by about 15 feet wide. Filled with display cases which are numbered. The display is calendar and theme based, so you start with very early days where iron clocks (see below) were made to the maritime clocks to the pocket watches to the 20th century. On the right hand side, you see a massive plaque on the floor which has got the major contributors (I guess) named in there).

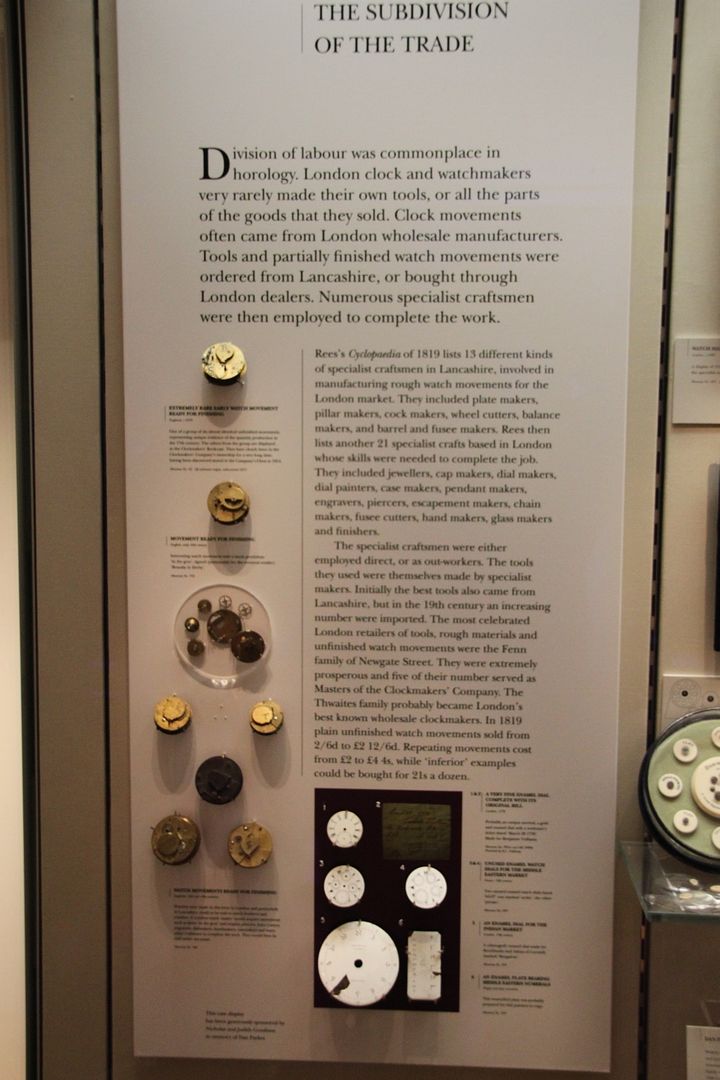

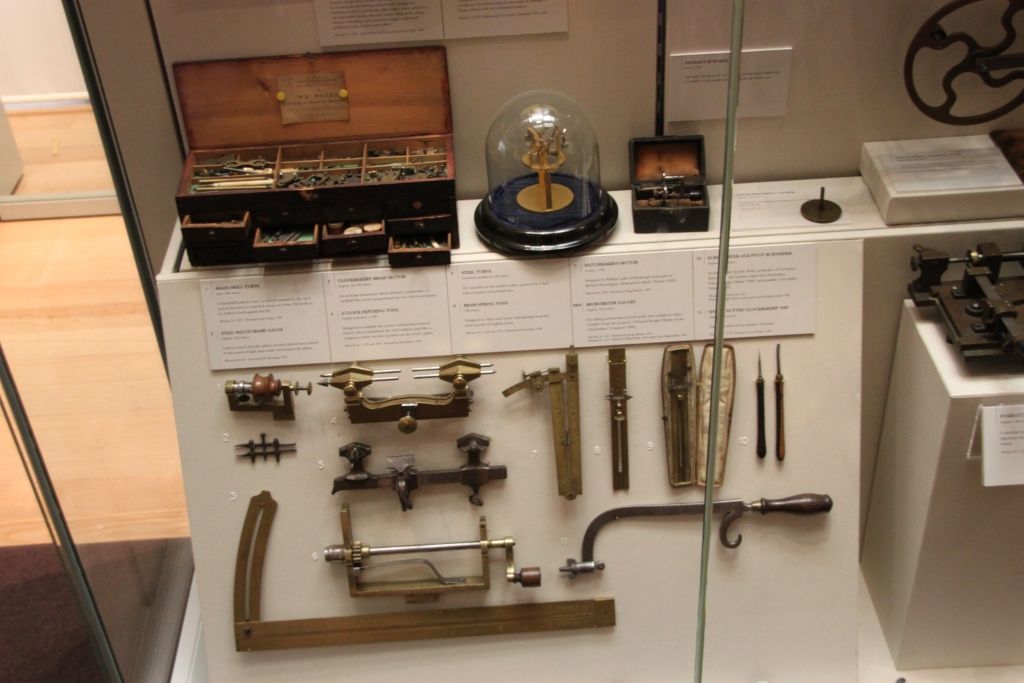

Watches and clocks were not made by one person alone in the 18th century, there was quite a lot of specialisation. At one point, there were tens of different types of specialist craftsmen such as plate makers, pillar makers, cock makers, wheel cutters, balance makers, barrel makers, fusee makers. These were making the basic clock/watch movement. Then you would have jewellers, cap makers, dial makers, dial painters, case makers, pendant makers, engravers, piercers, escapement makers, chain makers, fusee cutters, hand makers, glass makers and finishers. Then you had craftsmen who would make the tools that these clock craftsmen would use. And then you would have people who would supply the materials such as metals, paints, enamel, jigs, etc. etc. It was a big solid proper industry. For such a small end result, the industry was pretty big. This photo of a display shows the various components of a watch and some of the old makers (some of whom were part of the worshipful company of clockmakers).

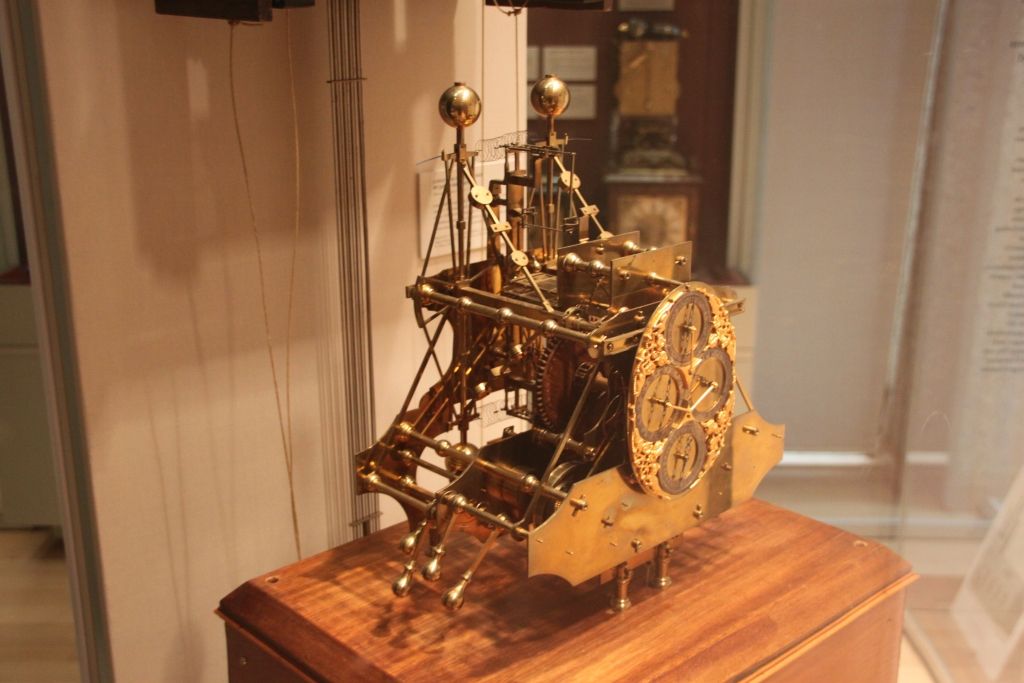

Two clocks separated by couple of centuries. The one on the left is from Germany, made out of iron, in the 15th century, while the one on the right is made in the 17th century. Strikingly similar in shape and function.

Two more clocks, these are of much more recent provenance in the 19th century but again, highly complex.

Watches, clocks and intricate work in the 17th century.

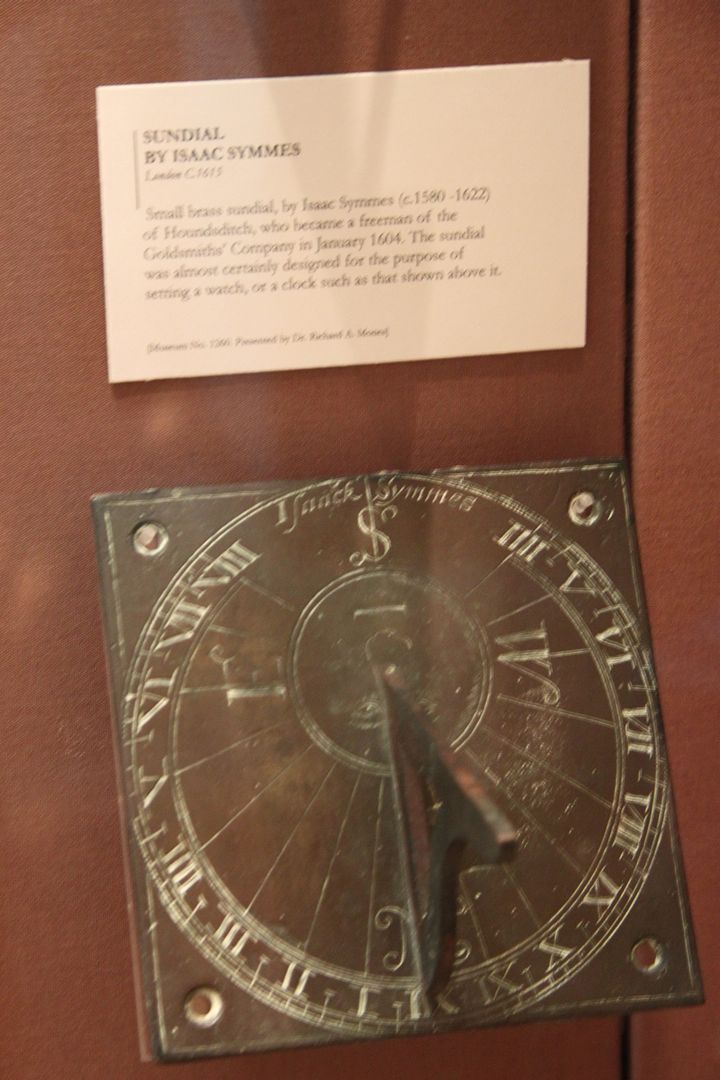

And the old sundial, made in 1615. These sundials were used initially to reset clocks. The accuracy of clocks at that time was not really that good and because of the metal used, the poor workmanship and lack of delicate movements, could lose up to an hour or two every day. Hence sundials would be used to recalibrate clocks and watches.

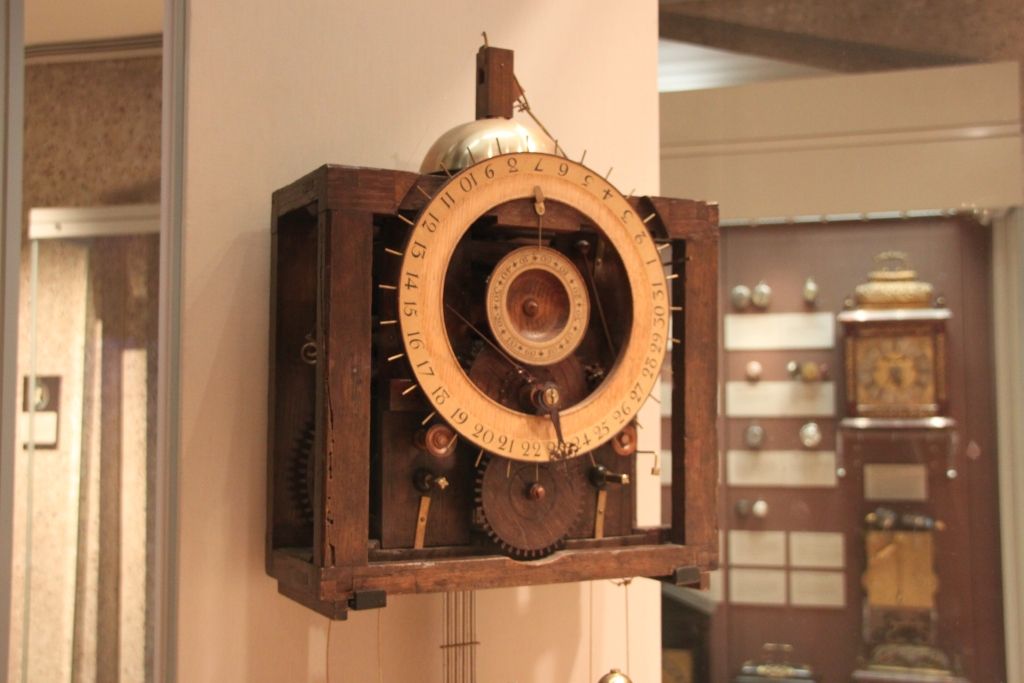

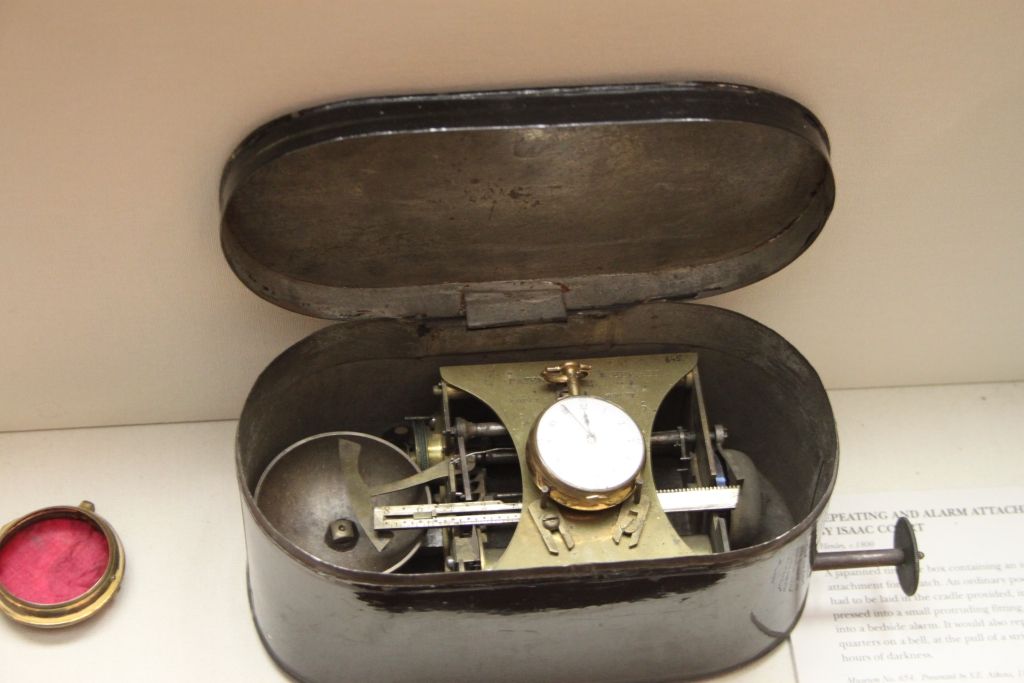

One of the earliest alarm clocks made in 1800. You come back home, then press your pocket watch into the centre, adjust the lever to specify the hour you want to wake up and the rotating square at the back of the watch will trigger ringing the bell. Also, by pulling a string, you could make it ring out the quarters and hours, very useful when its dark at night. Coolio

A model of what a watchmaker’s workshop could look like in the 17th century.

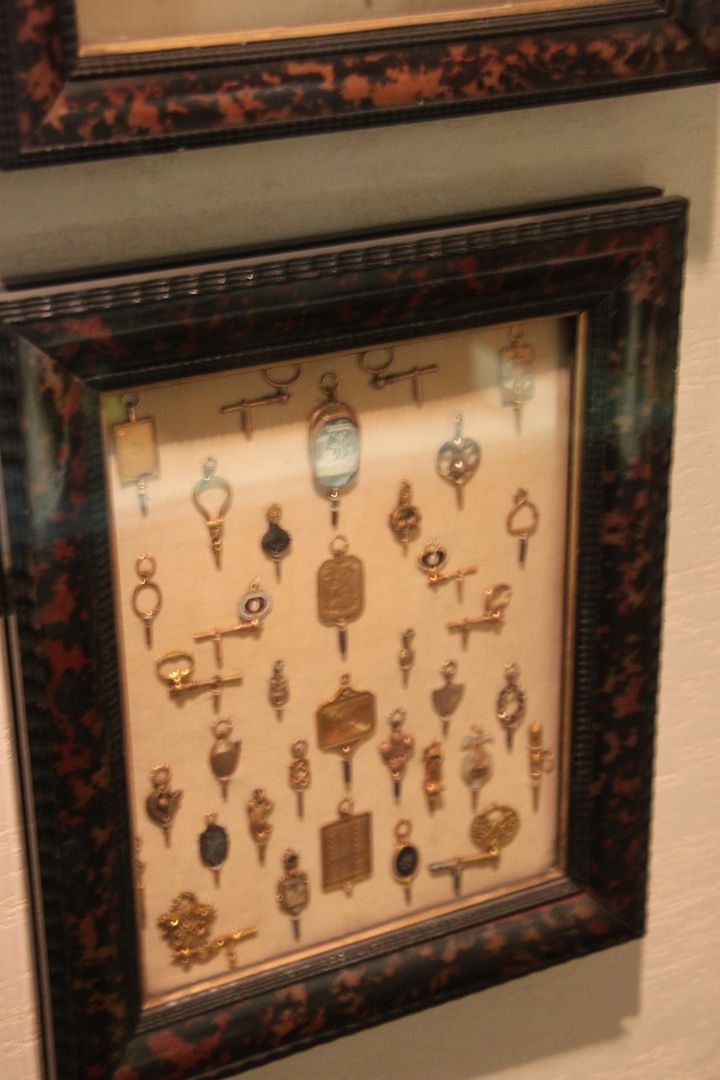

These are watch keys with different toppings, one would use them to wind up your watch.

Two examples of pocket watches made in the UK in 1640 and 1650 respectively. Now that’s fine work for you.

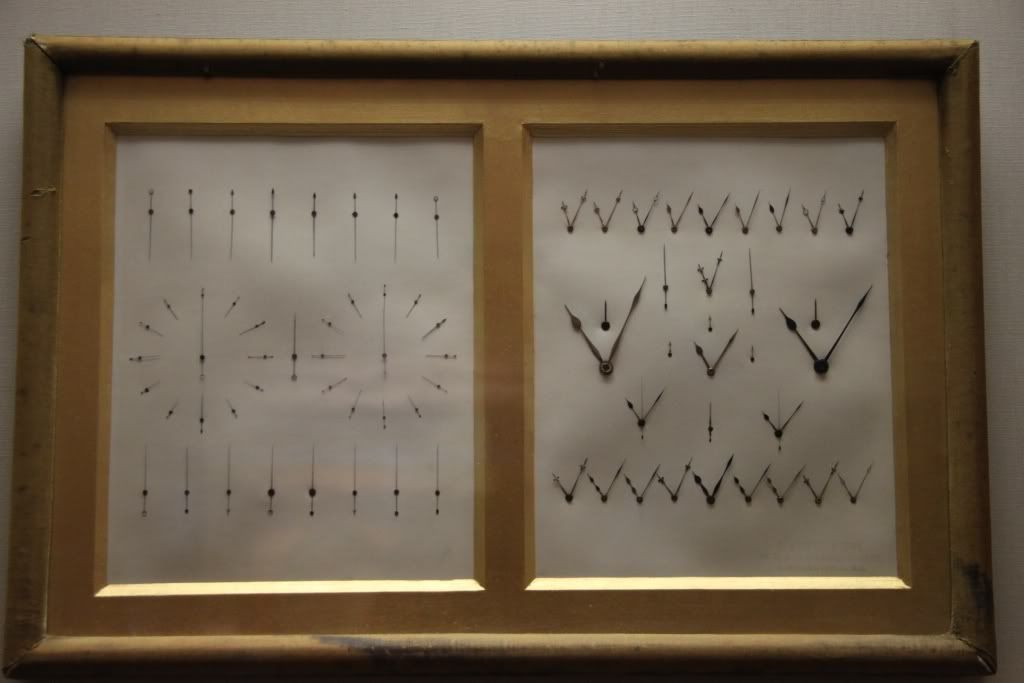

Watch hands, tools and some more watch winders in these three photographs.

One of the early marine chronometers made by Brockbanks in 1810. You can see how its been hung from gimbals to make sure that its always horizontal despite it pitching and moving around.

Some examples of grandfather clocks and watches made between 1666-1700 AD.

This watch movement was made by Thomas Mudge in 1755 and contains perhaps the world’s first thermostat.

A longcase grandfather clock. In the middle, you will see hand written tables which would provide time values, this is dated back to 1738.

A selection of watches which one would find at home in the 18th century.

A pocket watch showing mean time and sidereal time by George Margetts in 1798.

two astrological clocks. The one on the right was made in 1828 by Qi Mei-Lu in Wuyan Province in China based upon a model originally made by Father Verbiest in 1680.

Another example of a marine chronometer made in 1830 with seconds in the lower dial.

An extraordinary clock which shows the movement of some of the heavenly bodies, days of the week, month, time, and and and, all this using clockwork. How amazing.

The final clock was very eye catching. Made in 1920, it is controlled by this ball rolling up and down this plate. In one year, this ball rolls 2522 miles up and down the plate. Very hypnotising.

It is a small museum as I said, and not many people even know the existence of this museum. Did not see anybody in there but then, I suppose the inclement weather (it was pouring with rain) and the rather boring old subject matter might explain some of the low attendance. But if you are interested in history and manufacturing, then a trip to this museum is a must. Strongly recommended and its free.

No comments:

Post a Comment